Walker Percy is my favorite southern novelist. After reading that sentence, a few people will shake their heads and glance over at the Southern Author’s Roster on the wall. (Every home south of the Mason Dixon line has one). It is there where Percy falls deep into the double digits, well under the all-capped shadows of Faulkner and Capote. But those people probably never read Percy, or they’re just afraid to admit Faulkner kicked their literate ass.

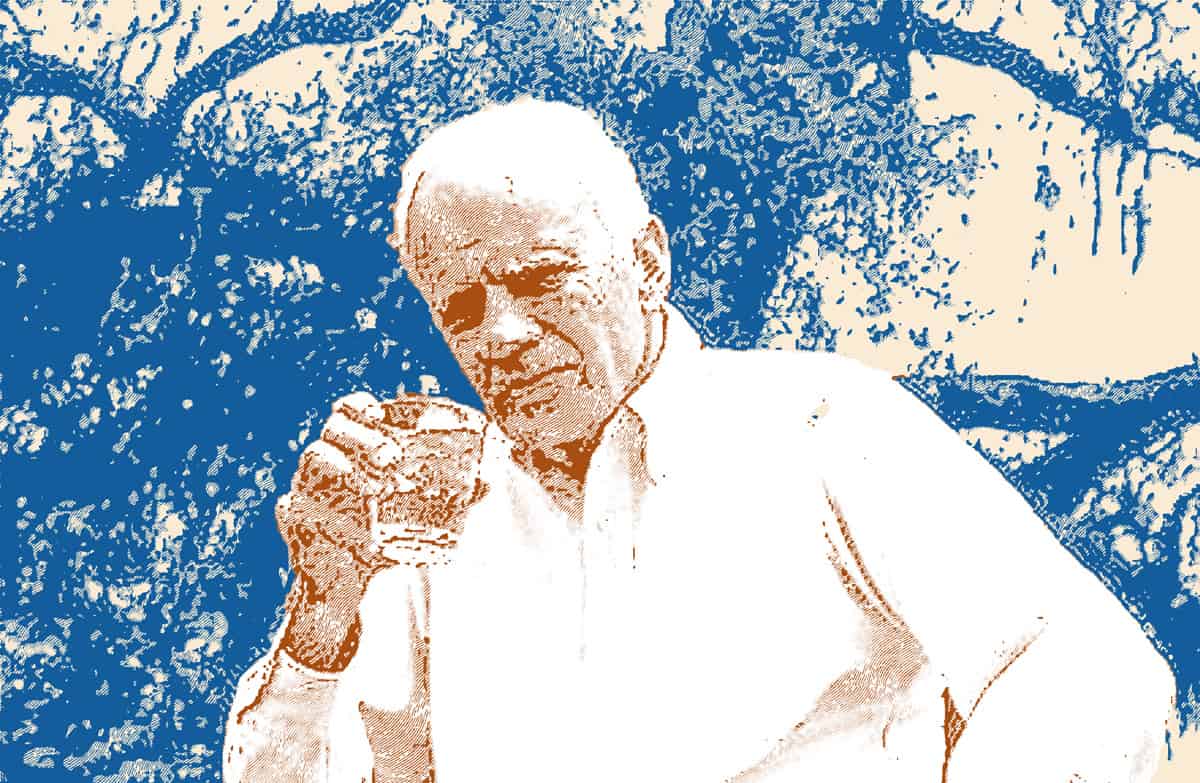

Walker Percy was a doctor by trade, a novelist by accident, and a philosopher by habit.

His first novel, The Moviegoer, hit me as strongly as any I’ve ever read. It’s right up there with Coming Through Slaughter (the greatest southern novel written by a Canadian) for its emotional right hook. But the emotions of The Moviegoer aren’t the bitter, drunk, stupid passions of Tobacco Road or the raw horror of Slaughter. Those are easy emotions to locate. Writing about them offers an opportunity to paint lush pictures with the palette of the human emotional color wheel. But most writers don’t come anywhere near Michael Ondaatje or Erskine Caldwell’s efforts.

Percy’s emotional palette was the strange and wistful ennui of the modern era.

The Moviegoer hit the stands in 1960 (winning the Booker prize in 1962). But its exploration of one man’s search for God and meaning in a world where technology’s rapidly advancing promises seemed to ensure prolonged happiness and abundance could not be more relevant to the sheer philosophical and spiritual fuckery of 2021.

The late 50s were interesting years for American intellectuals.

Something in the water affected the spirits of writers and artists. You have the beat poets, led by Kerouac and Ginsberg. You have the sudden appearance of the outsider. He appeared in luminous portrayals of dislocated men from James Dean’s work in Giant to anything starring Marlon Brando. Colin Wilson wrote about it in The Outsider. German philosopher Joseph Pieper wrote about the importance of “philosophical leisure time”. He said the people best suited to recognizing creation for what it was were the homeless. The wayfarers. They had the sense of wonder necessary to “preserve our apprehension of the universality of all things in the midst of the habits of daily life.”

Percy came at the same emergent wanderlust from a different angle

Percuy was a doctor and a Catholic. He started his career in medicine. But he contracted tuberculosis. He had to abandon his career for a prolonged period of rest (the only treatment for TB at the time). Percy spent that time in a sanitarium, reading and listening to World War II radio reports before being discharged. He worked in medical teaching briefly but eventually turned to writing.

The protagonist in The Moviegoer experiences similar ennui and revelation as Kerouac. (Those of you studying literature may find yourself infuriated about that, to which I say, respectfully, come at me, bro). But instead of wild road trips and globe-trotting dope-fueled run-on sentencing, Percy chose to pour a bourbon, neat, and write it all down. Carefully. The epiphanies of the beats seemed to burn them out. Where the epiphanies of the mid-century Catholic intellectuals like Percy seemed to bathe them in a gentler light. Both schools are vital, both concern themselves with the divine. But it always seems to me that Kerouac appealed to me in my 20s, yelling at me from the open window of a passing car on its way to God knows where. Percy spoke to me like he was wearing a sweater vest and sitting in his den.

Percy loved bourbon

His 1975 essay, “Bourbon, Neat” written for Esquire, was an entertaining testament to his relationship with Kentucky’s most important export. He summed it up perfectly here: The pleasure of knocking back bourbon lies in the plane of the aesthetic. But at an opposite pole from connoisseurship. My preference for the former is or is not deplorable, depending on one’s value system—that is to say, how one balances out the Epicurean virtues of evocation of time and memory and the recovery of self and the past from the fogged-in disoriented Western world. In Kierkegaardian terms, the use of Bourbon to such an end is a kind of aestheticized religious mode of existence, whereas connoisseurship, the discriminating but single-minded simulation of sensory end organs, is the aesthetic of damnation.

And in this remarkable passage:

“Not only should connoisseurs of bourbon not read this article, neither should persons preoccupied with the perils of alcoholism, cirrhosis, esophageal hemorrhage, cancer of the palate, and so forth—all real enough dangers. I, too, deplore these afflictions. But, as between these evils and the aesthetic of bourbon drinking, that is, the use of bourbon to warm the heart, to reduce the anomie of the late twentieth century, to cure the cold phlegm of Wednesday afternoons, I choose the aesthetic.

— Walker Percy, in Esquire, 1975

Then he finishes with this amazing, relevant bon mot

What, after all, is the use of not having cancer, cirrhosis, and such, if a man comes home from work every day at five-thirty to the exurbs of Montclair or Memphis and there is the grass growing and the little family looking not quite at him but just past the side of his head, and there’s Cronkite on the tube and the smell of pot roast in the living room, and inside the house and outside in the pretty exurb has settled the noxious particles and the sadness of the old dying Western world, and him thinking: “Jesus, is this it? Listening to Cronkite and the grass growing?”

W.P., Esquire, 1975

If you haven’t read the essay, just go there now and read it. But do yourself a favor and pour a jigger of whiskey out for yourself to refer to, preferably Old Crow, Percy’s most likely bourbon of choice.