My dad had a massive stroke two years ago. I was packing to leave for the UK the following day to start business school at the University of Oxford when I got the phone call. He had been standing at the kitchen sink rinsing the dinner dishes when he collapsed. My stepmom said he was like a puppet whose strings got cut: he dropped straight down to the floor without a sound. I got the next available flight to North Carolina. Touch and go in neurological ICU for three days. Ten days in a private hospital room at Wake Forest Medical Center. An endless series of discussions with surgeons, doctors and nurses. In-patient stroke rehab center for nine months. Home healthcare workers daily ever since. He doesn’t live close by – an 11 hour drive from Chicago – so it’s been periodic visits since for six, seven, 10 days at a time then longer stretches of trying to help from far away.

The details are different for every family, of course, but the theme is becoming more common among my friends and peers: we’re in our 50’s now and faced with caring for parents who are in their 70’s and 80’s. It’s an emotionally complex road to travel.

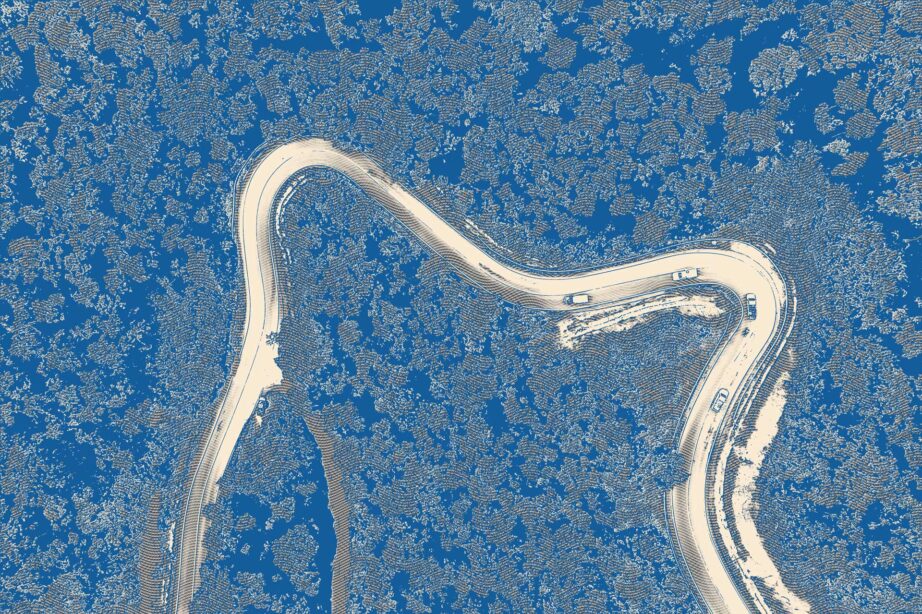

Well, not a road really.

A road is for driving in a car or riding a bike or walking. A road suggests that you have a say in the direction and speed and mode of traveling it. You’re in control on the road. This feels more like someone pushed you into a dark subway car alone and the train pulls out of the station really fast but you don’t know exactly how fast because you’re not driving and you can’t see shit cuz its dark and because its dark you can’t see the bend in the tracks so you keep losing your balance but you recover and don’t quite fall down then every once in a while you briefly can see shit cuz you’re stopping at a lit subway station but you can’t get off cuz the door doesn’t open but sometimes you don’t stop at that station you just speed right through the lit stop cuz who the hell knows why it didn’t stop and then its just dark and fast again and you have no idea when the next lit station is going to emerge from the dark or when this journey is gonna fucking end and you’re not sure you want this unpleasant journey to end cuz you know how much the end ends in a permanent, devastating loss that there’s no coming back from.

More like that. So less like a road, I guess.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m very grateful my dad is alive. It feels like there is still so much more to say to each other. And I’m grateful for the advances in healthcare over the past 20 years that allowed my father to survive this event. Continual advances in healthcare technology saves lives now that would have been unquestionably lost even just a couple of years ago. New drugs and surgical methods and imaging tools and AI systems are extending lives in unprecedented and uncharted ways.

But here’s the thing: technology is not just extending life. It’s extending death, too.

This stroke would have killed my father even five years ago. He’s still with us. His death is just in slow motion now. Now he’s dying from this stroke over a few years rather than in a few minutes or hours. Don’t misunderstand: I’m glad he’s still here. But he is shuffling off this mortal coil in slow motion. Is that better or worse? It doesn’t really matter. That’s not a relevant or even interesting question, if I’m being completely honest. It’s a distraction into hypotheticals when attention and focus needs to remain on a hard, unadulterated reality.

The journey of caring for aging parent usually begins with a singular event that changes everything: a heart attack, a stroke, or maybe that first time your mom tells you her sister is coming to dinner on Sunday even though her sister died twelve years ago. It’s a point-in-time crisis that the family rallies around, and it creates focus and common cause and an outpouring of love and devotion. This is a parent who raised us, nurtured us, supported us. Or maybe they didn’t raise or nurture or support us, but we eventually found a way to make peace with that. Or maybe we didn’t find peace with that at all. Every family’s story is different. But the emotional connection, whether its what we have or what we wish we had, is deep-rooted and it propels us into the role of caregiver. We want to give back to them the care and support they once gave us. Or wish they had given us.

For me, I love my dad. In my teens he made a few mistakes as a husband and a parent, I made a lot of dumb teenager mistakes towards him that I regret. We grew past it. And we grew towards each other. Our adult relationship has been healthy and nurturing. He’s extremely proud of who I am and what I’ve done with my life and he tells me that often. And I recognize that who I am and what I’ve accomplished is grounded in the many of the values he taught me, and I tell him that, too. Work hard, earn what you get, remember the janitor’s name not just the CEO’s, repay with discretion when someone trusts you enough to confide in you, don’t be an asshole. Valuable life lessons. Especially that last one.

So to see my “strong as an ox” dad unconscious in an ICU hospital bed was a gut punch that started a long chain of emotionally, intellectually and logistically difficult questions. How to care for his immediate medical needs while trying to anticipate the next ones coming. Having the painfully real discussion of his criteria for a “Do Not Resuscitate” order. Getting an unambiguous understanding of where and how he’d like to be buried. Finding a home health care company and making sure they show up when they said they will. Helping to make sure his final affairs are in order. So many of my friends and acquaintances all seem to be confronting a similar set of questions for their parents lately. None of these questions have easy answers.

So what whiskey do I drink when I’m pondering how to care for my dying father? I don’t drink any whiskey at all when I need to spend time with that question. Instead, I give him the appreciation and respect to think through with clarity the best options for his care and comfort and final wishes. And the love to spend time with my memories of him with a clear head. But sometimes in those brief “in between” respites, when I smile because some random happy memory of my dad crosses my mind, I might have a sip of Defiant American Single Malt and quietly thank for my father for who he has been to the people around him.