The Birth of Good Bourbon for a Good Cause.

At three in the afternoon on August 26, 2017, Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas coast with 130-mph winds and 40 inches of rain. It wiped out Port Arkansas. It flung a cargo trailer into the Rockport courthouse. It hammered and flooded every home in Holiday Beach. Across the bottom of the state, more than 300,000 structures were leveled. More than half a million vehicles smashed, sunk, or blown away. Houston was underwater. Families huddled together on their roofs and prayed.

Just over 250 miles away

Dan and Nancy Garrison, of Garrison Brothers Distillery, watched Harvey tear into Texas. They saw businesses they knew—like Spanky’s Liquors in Port Aransas—flattened. Nancy couldn’t stand it. She wanted to drive down there and help. So did Dan, but it was a bad idea. He knew they’d just run out of gas, end up stranded, and become part of the problem instead of the solution. The people marooned on their rooftops needed solutions. Dan looked at the destruction and wondered what the hell a guy making bourbon in the middle of nowhere could do. Then he picked up the phone.

Garrison called a friend at Team Rubicon who was involved in rescue efforts and asked a simple question: “What do you need?” His friend gave him a simple answer: “We need boats.”

Garrison didn’t have any boats

But he had nine barrels of a limited-release bourbon. It had four years to wait before they could bottle it and sell it to the hundreds of obsessed bourbonites who would line up down the long dirt road to the distillery. Garrison realized those barrels represented thousands of dollars he could direct toward relief efforts. Toward boats. Toward those people strewn across the coastal counties without power or water or a place to sleep. He had that.

That night, Garrison and his team put together a website to presell those bottles as a fundraiser. They named the bourbon Hurricane Tough. Of course, there was no way to know if anyone would buy a bottle of bourbon they wouldn’t see for another four years. There was no guarantee.

They raised $20,000 in the first hour and $144,000 by the end of the week. That money bought a small fleet of boats, saved a bunch of people, and gave Dan Garrison measurable proof of something he’d always believed:

People who drink bourbon are good people.

So are the people who make it. When you think of whiskey culture, your mind tends to flash images of rugged elegance. Your mind plays slow-motion commercials of cowboys around a fire lifting a tin cup full of bourbon and laughing at a joke you can’t hear. Your inner theater plays a clip of a bartender diligently building a sepia Manhattan in a frosted coupe. You think of a serious conversation with old friends. You think of country music and blues guitars and Texas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. You don’t think—you don’t usually think—of volunteerism.

Dan Garrison might change all that.

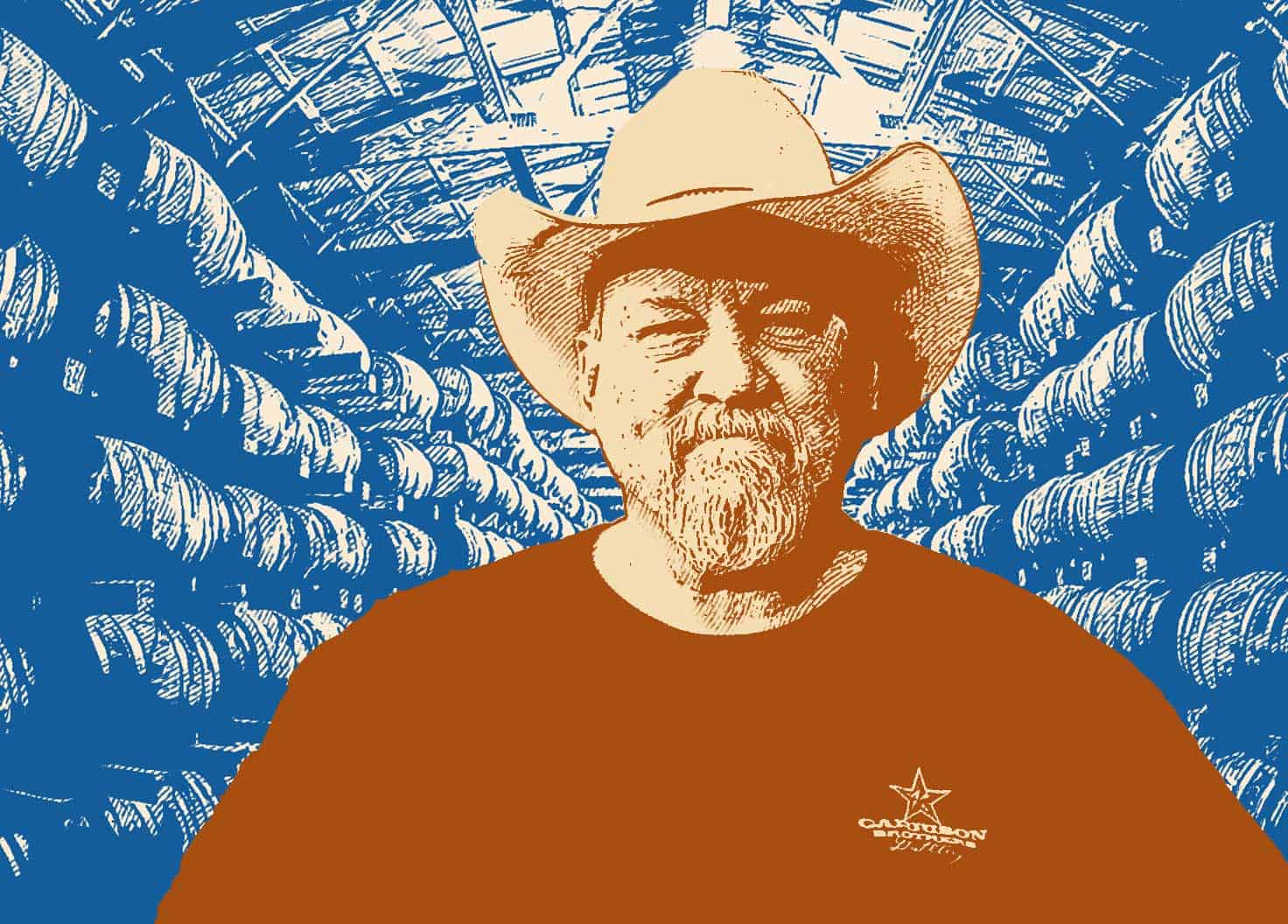

You wouldn’t call Garrison subtle. In conversation, he tends to get to the heart of the matter. Not in a blunt or macho way—he’s not like that. More like a teacher. He appreciates clarity. Brevity. In politics, especially those narrowly focused, hyper skirmishes between Texas distillers and the Texas congressional house on the “bottle bill,” Garrison’s opinion is stated firmly enough that everyone can hear at the back of the room. In business, the man has built a widely recognized brand of bourbon in a state that’s not exactly helping him while competing against whiskeys with household names, global reach, and billions of advertising dollars. And if the image of Garrison you’re building in your mind’s eye right now is 75 percent cowboy, you’d be about 20 percent right—but you’d also be missing the most important element of this slightly larger-than-life, purely American, purely jeans and a t-shirt Texan; you’d be missing the overlooked virtue that’s fundamental to his success, the thing that drives his charitable ambition:

Dan Garrison’s got a 53-gallon heart

This matters. It matters because the trend of wildly successful entrepreneurs in the US does not point toward charity. Except in the whiskey business. Directing a distillery’s influence and profit back into the community where it’s made, to the people that serve it, bottle it, and even drink it, is trending.

Angel’s Envy, High West, and Heaven Hill all support charities. Bourbon Charity, a non-profit with more than 12,000 supporters, has raised nearly a quarter-million dollars in 2021 for Children’s Tumor Foundation, St. Jude, Feeding America, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Autism Speaks, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

It matters because it supports the simple underlying concept of Garrison’s charity—that bourbon people are good people. Hence, their call to action: “Drink well. Do good.”

Which is not merely a slogan.

Garrison lives this motto. Look at the story Garrison tells of how he hired master distiller Donnis Todd, who essentially just showed up one day at the distillery. Garrison asked him who he was and what he wanted, and Todd said, “I want to help you make the best bourbon in the world.” Garrison sized him up and said, “All right.” Hired him on the spot.

Now, surely there are gaps in this story; surely there was a much longer conversation wherein Todd explained his family history of whiskey making, how he interned in Korean distilleries when he was just out of the air force. But the nutshell version is that Garrison recognized a kindred spirit and a sincere veteran, and his heart said, Hire this guy. So he did.

Good Bourbon for a Good Cause (GBGC) puts veterans to work.

There are four pillars of focus at GBGC: community relations in Texas; wide-open spaces; hospitality workers; and veterans affairs. Those last two come directly from Garrison’s experiences.

In Houston, he took a meeting with a bartender who was thinking about carrying his bourbon. The bartender shambled in on crutches a half-hour late in a flurry of apologies. Garrison noticed the guy didn’t have a cast and the crutches made mixing drinks damn near impossible. Plus, the poor guy was clearly in great pain—yet he came in to work his shift because he didn’t have health insurance or paid medical leave. This didn’t sit well with Garrison. Here’s one of the pillars of the spirits industry, the last link in an important and lucrative chain, and he can’t even get a cast for his broken leg? Can’t even take a day off?

Garrison learned that a lot of veterans return from active duty to civilian life with a host of problems, PTSD being at the top of the list. But another problem, one that doesn’t get as much press, is a sudden lack of direction. Veterans returning to civilian life after combat often find themselves somewhat adrift. GBGC helps fund and staff Team Rubicon, a nonprofit organization that leverages veterans’ unique skills to work in disaster relief.

“It puts them in harm’s way,” explained Garrison. “It gives them a sense of mission purpose.”

Which leads to the enduring driving force behind GBGC.

It’s pretty simple. Talking to Garrison, it’s clear the fundamental motivation for his charity is a natural extension of his personality. Throughout the interview, he constantly referred not to himself but to the people who work in his distillery, the people who volunteer there during bottling season. His references were funny. The kind of homespun, charming tales you expect from any respectable Southerner (ahem). But they were also telling a story that was heartwarming. As those strangers come together to help bottle bourbon, they form an enduring bond—not only with each other but with Garrison and his staff. It seems like it’s part of Garrison’s nature that he is always building a family. It’s not exactly in the motto of the charity, but it’s there. It’s at the heart of it.

“People—bourbon drinkers—are interesting people,” said Garrison. “They like to socialize. And of course, they like to drink good bourbon. I’ve seen how bourbon connects people. Good bourbon creates solidarity. Solidarity creates family.”

In technical terms, in the language of social science and psychology, Garrison is helping people integrate. Veterans find a niche that connects them not to the destruction of life but its preservation—which integrates them into that broader community. With volunteers, he’s bringing them together in an atmosphere that just doesn’t feel like work—a place where they form lasting friendships and partnerships. For bartenders, he pulls them in and lets them know they are not alone, not weeded, not abandoned but cherished. Supported.

All of these serve a noble purpose. (I am certain that when Garrison reads that sentence, will choke on his whiskey.) Isolation is a terrible thing. Trace most of the worst things that ever happened, and you’ll find a lonely, isolated, disconnected person right at the front of it.

To discover instead that you are useful, that you have a purpose, that you have people . . . this is joyous. This is, after all, what it—what life—is all about. Garrison knows this, and he is not at all shy about it:

“Good bourbon,” Garrison explains, “can change the world.”

4 thoughts on “Dan Garrison’s Bourbon Barrel-Sized Heart”